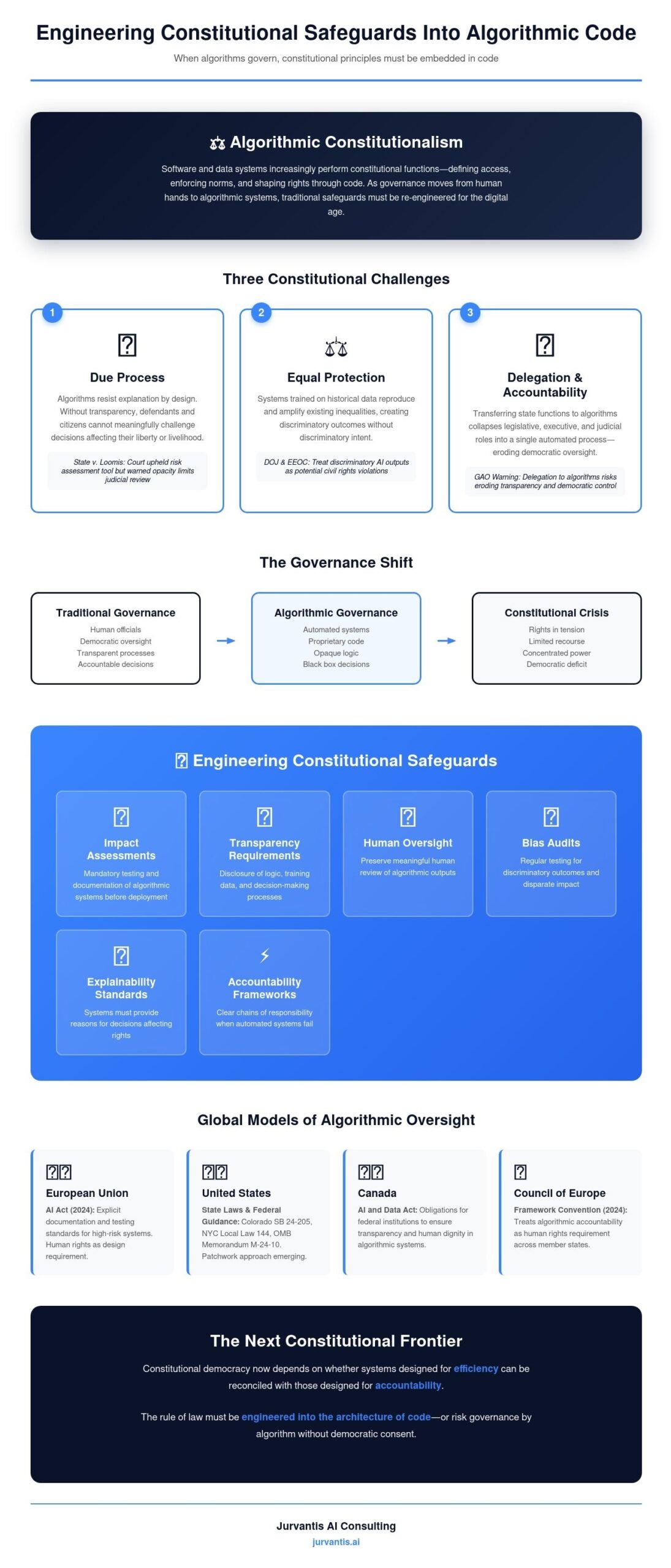

Engineering Constitutional Safeguards Into Algorithmic Code

The rule of law was written for human hands. Yet as governments and corporations rely on algorithms to filter speech, allocate benefits, and predict behavior, power increasingly resides in systems no one elected. The rise of algorithmic constitutionalism marks a turning point: when governance by code begins to shape the rights and limits once guarded by constitutions.

The Constitution Inside the Machine

Algorithmic constitutionalism refers to the idea that software and data systems increasingly perform constitutional functions, defining access, enforcing norms, and shaping rights through code. The concept builds on legal scholar Mireille Hildebrandt’s work on the constitutionalism of technology and on Lawrence Lessig’s observation that code is law. Together, these frameworks argue that algorithms now operate as instruments of governance, often without democratic oversight.

From facial recognition in policing to automated credit scoring and social media moderation, these systems decide who is visible, credible, or eligible. They determine access to housing, education, and employment. In effect, they legislate conditions of participation. The constitutional question is no longer whether algorithms should be regulated but how traditional principles of due process, equal protection, and free expression apply when governance happens inside a machine.

Due Process and the Right to Be Heard

Procedural fairness, the foundation of constitutional governance, depends on explanation. Yet algorithms often resist explanation by design. In State v. Loomis (Wis. 2016), the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the use of a proprietary risk assessment tool in sentencing but warned that its opacity limited judicial review. The court recognized that without understanding how a system reached its conclusions, defendants could not meaningfully challenge them.

A similar issue appeared in Houston Federation of Teachers v. Houston ISD (S.D. Tex. 2017), where teachers sued after being evaluated by a secret algorithm that determined pay and employment. The court ruled the system violated due process, holding that decisions affecting livelihood must be subject to review. Across both cases, the principle is consistent: due process requires more than outcome accuracy. It demands transparency and accountability.

International frameworks mirror this view. The European Union’s AI Act, which entered into force on August 1, 2024, mandates that users of high-risk systems document logic and testing methods. The United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office emphasizes a similar right to human review. These approaches treat explanation as a procedural safeguard, not a technical courtesy.

Equal Protection and Discrimination by Design

Algorithmic bias has evolved from a software problem into a constitutional one. Systems trained on historical data can reproduce or amplify existing inequalities. In the United States, this implicates the Equal Protection Clause when automated decisions disproportionately affect protected groups.

The Joint Statement on Algorithmic Fairness issued by the Department of Justice and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2024 treats discriminatory AI outputs as potential civil rights violations. The agencies drew parallels to landmark cases like Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886), where a facially neutral licensing law was applied in a racially biased manner. The modern version of that logic lies in algorithmic systems that appear impartial but perpetuate systemic bias.

Predictive policing tools can reinforce patterns of over policing in minority neighborhoods. Automated hiring filters may exclude candidates based on proxies for disability or gender. These systems may lack intent but still yield discriminatory outcomes, raising the question of whether algorithmic action counts as state action. Courts have yet to fully decide, but the constitutional implications are clear. When government or its contractors use biased models, the Fourteenth Amendment still applies.

Delegation and Accountability in Automated Governance

Delegating state functions to algorithms presents a modern version of the nondelegation problem. When agencies use predictive systems to assess benefits, parole, or tax compliance, they transfer discretion from public officials to private code. The Government Accountability Office warned in its 2023 AI Accountability Framework that such delegation risks eroding transparency and democratic control.

The White House reinforced this concern in its OMB Memorandum M-24-10 on federal AI governance. The guidance requires agencies to ensure human oversight and document system limitations. These measures serve a constitutional function by preserving the traceability of state action and ensuring that decisions remain accountable to law rather than logic alone.

Delegation also raises issues of proprietary secrecy. Vendors often cite trade secrets to avoid disclosure of model logic, putting constitutional rights in tension with intellectual property. Courts may soon have to decide whether due process outweighs commercial confidentiality when liberty or livelihood is at stake.

Private Platforms and the Quasi Constitutional Role of Code

Beyond government use, private algorithms now shape core public freedoms. Social media moderation systems decide what speech remains visible, creating what scholars call private constitutions. These systems blend rulemaking and adjudication without public accountability. The tension is visible in NetChoice v. Paxton, a Texas case challenging whether platforms’ moderation decisions qualify as expressive activity under the First Amendment. In July 2024, the Supreme Court vacated and remanded the case, requiring lower courts to conduct more thorough First Amendment analysis of how state laws regulate social media content moderation.

Platforms simultaneously claim the rights of private actors and the authority of regulators. Their automated systems apply global norms, removing speech, labeling content, and ranking visibility. The European Union’s Digital Services Act acknowledges this role by requiring large platforms to assess systemic risks and disclose how algorithms shape public discourse.

These developments signal the rise of algorithmic constitutionalism in practice. Governance now occurs through technological infrastructure rather than state institutions. As these systems mediate civic participation, constitutional oversight must extend to digital architectures themselves.

Re-engineering Constitutional Safeguards

Efforts to restore transparency are multiplying. Colorado’s SB 24-205, enacted in May 2024, requires deployers of high risk systems to conduct impact assessments, maintain documentation, and disclose risks. These obligations echo due process values of notice, justification, and review reframed for algorithmic decision making.

At the professional level, the American Bar Association’s Formal Opinion 512, issued in July 2024, clarifies that lawyers using AI must supervise outputs, verify citations, and document human review. The opinion aligns ethical responsibility with constitutional accountability. Professional duty mirrors the state’s obligation to ensure human oversight.

Other jurisdictions are following suit. New York City’s Local Law 144, which began enforcement in July 2023, mandates annual bias audits for hiring algorithms. The Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence, opened for signature in September 2024, codifies transparency and proportionality principles for algorithmic use across member states. These frameworks effectively constitutionalize algorithmic governance by embedding checks and balances within AI system design and deployment.

Global Models of Algorithmic Oversight

Algorithmic constitutionalism is not uniquely American. The European Union’s AI Act sets explicit documentation and testing standards for high risk systems, while the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention treats algorithmic accountability as a human rights requirement. These frameworks reflect a constitutional philosophy that law must remain superior to code.

Other regions are moving in parallel. Canada’s Artificial Intelligence and Data Act proposes similar obligations for federal institutions, and Brazil’s PL 2338/2023 emphasizes algorithmic transparency under its constitutional right to equality. Across these efforts, constitutional language of human dignity, accountability, and due process reappears as the lexicon of algorithmic governance.

Algorithmic Power and the Separation of Functions

Constitutional systems depend on separating powers to prevent concentrated control. Algorithms, however, collapse legislative, executive, and judicial roles into a single process. They define rules, execute them, and generate outcomes simultaneously. This fusion challenges traditional oversight mechanisms. When prediction replaces deliberation, the balance among branches tilts toward automation.

Courts are beginning to push back. Federal judges across multiple districts have issued standing orders requiring certification of human review for AI generated filings. According to Bloomberg Law’s tracking, as of April 2025, at least 39 federal judges have issued such orders since May 2023. These measures reinforce the constitutional demand for human reasoning behind legal argument, an echo of the broader principle that governance must remain intelligible to those it governs.

The Next Constitutional Frontier

Algorithmic constitutionalism is both a warning and an opportunity. It forces courts, regulators, and practitioners to translate constitutional values into technical standards such as explainability, documentation, and traceability. These requirements mirror traditional checks and balances in a new form. The rule of law persists, but it must now be engineered into the architecture of code.

Ultimately, the durability of constitutional democracy may depend on whether systems designed for efficiency can be reconciled with those designed for accountability. The future of AI governance will test whether legal principles can constrain algorithms as effectively as they once constrained kings.

Sources

- American Bar Association: Formal Opinion 512 on Generative AI Tools (July 29, 2024)

- Bloomberg Law: Which Federal Courts Have AI Judicial Standing Orders (April 16, 2025)

- Colorado General Assembly: SB 24-205 Consumer Protections for Artificial Intelligence (May 17, 2024)

- Council of Europe: Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law (September 5, 2024)

- Data Privacy Brazil Research: Artificial Intelligence Legislation in Brazil (Dec. 2024)

- European Commission: Digital Services Act Package (2024)

- European Union: Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 Artificial Intelligence Act (June 13, 2024)

- Georgetown University Law Center: “Affording Fundamental Rights: A Provocation Inspired by Mireille Hildebrandt,” by Julie E. Cohen (2017)

- Government of Canada: Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (2024)

- Hildebrandt, Mireille: Law for Computer Scientists and Other Folk (Oxford University Press, 2020)

- Justia: Houston Federation of Teachers v. Houston ISD, S.D. Tex. (2017)

- Justia: NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton, Fifth Circuit (November 7, 2024)

- Justia: State v. Loomis, Wisconsin Supreme Court (2016)

- Justia: Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)

- Lawrence Lessig: Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (Basic Books, 1999)

- New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection: Automated Employment Decision Tools (Local Law 144 of 2021)

- U.S. Department of Justice and EEOC: Joint Statement on Algorithmic Fairness in Employment (2023)

- U.S. Government Accountability Office: Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies (2023)

- White House Office of Management and Budget: Memorandum M-24-10 Advancing Governance, Innovation, and Risk Management for Agency Use of Artificial Intelligence (March 28, 2024)

This article was prepared for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. All cases, statutes, and sources cited are publicly available through official publications and reputable outlets. Readers should consult professional counsel for specific legal or compliance questions related to AI use.

See also: Delegating Justice: The Human Limits of Algorithmic Law

Jon Dykstra, LL.B., MBA, is a legal AI strategist and founder of Jurvantis.ai. He is a former practicing attorney who specializes in researching and writing about AI in law and its implementation for law firms. He helps lawyers navigate the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence in legal practice through essays, tool evaluation, strategic consulting, and full-scale A-to-Z custom implementation.